I'd love to hear more about your written introduction (published in Trese’s book Surface Streets), which is like a script for a LA-noir film.

I moved back to LA in 2007. At the time, I was living in Miami and decided it was time for a change. I drove cross country with my friend Justin. As we approached LA, even from 50 miles, there was a giant black cloud over the Western part of the sky. The fires and Santa Ana winds were really bad that year so It made the light have a grey-pink tinge. I guess it was Noir, sort of a dark-glam. But for both of us it was a fresh start as well. And I think that is how a lot of people see LA. A clean break. So, LA’s Noir can feel playful and a bit optimistic as well.

Are you nostalgic?

I can see how it could seem like that- I shoot a lot on film, and I do work across time and like to revisit the same subjects. But I am mainly interested in things that are happening now- I’m more drawn to the present than the past.

Does LA evoke a particular dream for you?

Of course- Hollywood. An esoteric lifestyle. The Wild West. Even more than that, I’m interested in the collective dream of what LA is to the people who live there and how that sometimes becomes a kind of effervescent backdrop for the city. A stage. Something that’s fake and light but maybe you believe it a little bit too. The reality is of course quiet different... But it’s a fantasy I don’t mind humming around in the background.

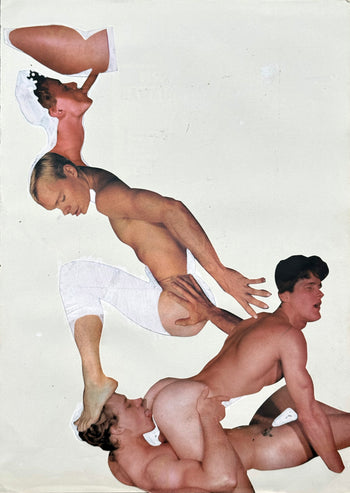

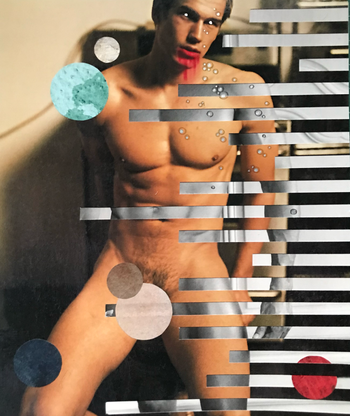

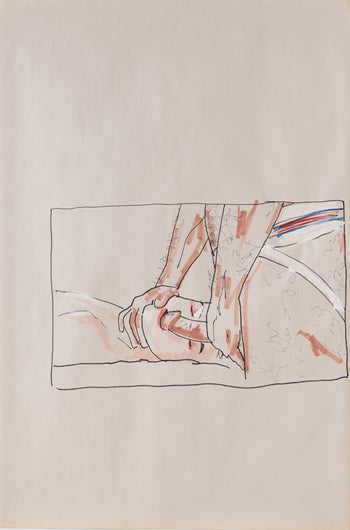

In Surface Streets, bodies often intermingle with architecture. Is this a queer gesture, as if to suggest the sensuality of our everyday surroundings?

I love that idea, yes. Suggesting the sensual on what we see every day is part of our history and feels very natural as a photographer.

You know, I was recently listening to someone who is now in their 80’s talk about his experience as a gay person living in LA in the 1950’s. The cops. The parties. The bars. Someone asked if the gay-bars were underground. “No, no,” he said, “They weren’t underground. They were right there on street level. Everyone could see them.” Of course, there was a bit lost in translation there. But I think this multi-generational miscommunication speaks to the fact that queer spaces have hidden in plain sight for so long. We’ve semi-claimed these alleys and beaches and buildings with a charged energy that is distinctly our own. It’s a gentle skill that we have developed since forever.

What does an inclusive artistic community look like?

I think that is such an important question. I also wonder what an inclusive queer community would look like and maybe more importantly feel like. Perhaps we are too far off to even make a guess. But, I think we can inch closer by actively supporting new disruptive voices that can move us forward. People like EJ Hill and Jonathan Lyndon Chase come to mind right away.

Your work is certainly in a long lineage of documentary photographers - queer and straight alike. How have you carved out a space for yourself?

It’s a bit hard to say at this point. I have worked as a photographer for a long time. Before that I was printer. And before that I studied Art History. It’s probably more intuitive now than it was when I started. But I still try to work with people that I respect and not to look back too much.

How do you cultivate intimacy as a photographer? Is this different than the intimacies you forge in your non-professional life?

I don’t think it’s different. I can’t really fake it if I’m not into it. As a photographer, I am always just trying to show other people why I’m inspired by the subject.

Do you ever fall in love with an image?

All the time! Usually something printed rather than through social media.

I recently visited Arthur Tress at his San Francisco studio and was able to see all his photographs with children from 1960’s and 70’s. His Dream Collector series is so amazing. Flying Dream, Queens, 1971 and Child Buried in Sand, 1968 have really stayed with me.

William J. Simmons is a queer/feminist writer, historian, and curator.