Making a Biopic of someone like Mapplethorpe is no small task. What was most important in executing your portrayal?

[Matt and I] tried to pull our punches in painting an unflinching portrait of Mapplethorpe as an artist. How he was uncompromising in his work and uncompromising is his life. The two feed each other, because we’re not separate as artists. Our art and our lives are not separate things. We’re one person, and when you’re an impossible visionary, you’re a person who takes on the impossible and has to withstand the ridicule and criticism of people in order to hold fast to your vision.

When did you get into filmmaking? And how did what you know about documentary apply to making a biopic?

I’ve had the most rewarding life. It’s hard work and it’s nonstop, and time is always this thing that I’m racing against, because there is just so much to capture… I was able with my camera to communicate to the outside world. To give [a person’s] life journey— which is usually filled with a lot of pain— some value. To create a bridge of empathy. That sold me on the power of the camera. I had not discovered a camera until I was 19 years old, and from then on it was nonstop. I only put the camera down when I had a baby, because I had to carry the baby, but that was only for the first few years. I do a lot of my own shooting, usually with another shooter as well. I shot all the Super 8 in the film actually.

I loved how you integrated old footage, too…

That was my documentary touch, but I feel like it grounds the story in history. I mean, in terms of making the transition from documentary to scripted— I wrote 58 drafts for this film. I did rewrites after the Sundance Lab to refine my vision for the budget. It was all helpful. It made me economize the words and the dialogue to get to what the core story really was. It’s Robert Mapplethorpe! I needed everything to feel as authentic as possible, and my doc skills really came in handy. The key is to be as authentic as possible so you can lose yourself in it.

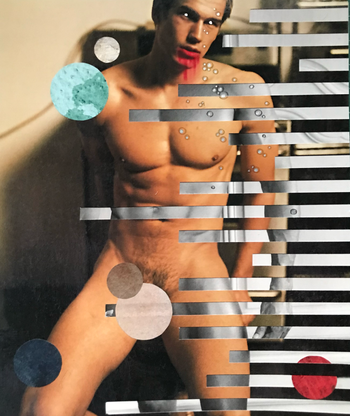

I noticed the attention to detail-- like the photos of Peter Berlin, and the really amazing nods to the queer community, not only the iconic imagery we associate Mapplethorpe with. How did you choose which photos were incorporated in the film?

I think it was a group effort with the producers. I mean we all weighed in on our favorite photographs. Nate Dushku was really the most active creative producer on it. [He’s] gay and had a lot of opinions regarding what he felt was most illustrative of what would speak to a gay audience.

And what about you?

I came from the perspective of understanding the human artist. The collision of art and commerce. The journey that Mapplethorpe's taken. The obstacles. Of course, as a storyteller, all my films have been about characters that take on the impossible and that are visionaries, and are tortured geniuses in a lot of ways. I’ve spent my whole career almost exclusively celebrating and studying those people to get audiences to feel empowered. To go and pursue their vision no matter how flawed they are. I chose, for example, The Good Knife and the Flower, cause I could build a story. I could come up with scenarios that would feed from his life and into these photos. Same thing with the champagne/penis shot. I wrote that whole party scene because I wanted to see him being playful. See him in his home. He’s saying “all these art collectors think they’re so avant-garde but they can’t even look at my photographs.” He calls it playing chicken with the avant-garde. I made all that up, but it culminates into the moment.

How many of the situations did you invent? And why did you choose to do something scripted rather than documentary?

I was never interested in making a doc. I love Randy and Fenton (who made that film), we’ve been friends a long time. I’m so studied on Mapplethorpe. I’ve been writing and working on my film since 2006, so when they showed up, we had the best time. I was grateful for their research, but I never had any interest in making a doc because usually my docs look forward and they’re suspenseful, and they’re current, and I wanted to bring Mapplethorpe to life. He’s a cultural lightning rod. He’s an outrageously sexy, vibrant human. Gorgeous guy. And I wanted to see him alive. I wanted to bring him alive. So to answer the question of what I made up… I had to imagine a lot of scenarios, it was very researched though. Patricia Morrisroe’s biography was really helpful and the Foundation sent me a lot of his books.

I was expecting more of Patti Smith. Was she involved in the production at all?

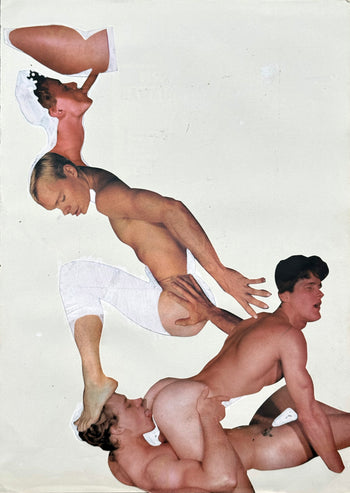

She was not interested in helping this or the doc for her own reasons. I didn’t want to completely lose the Patti relationship, even though she wasn’t really on board with this project, thought I tried many times to include her. And so, the questions became, what’s brought up— can you lose her from the story? Which I’m sure she would have preferred, but no. I couldn't lose the perfect trifecta of Robert coming of age as a human, growing up in the world, being an 18/19/20 year old lone wolf in New York, who finds his soulmate and then comes into his art. Ironically she pushed him towards [his art], and that’s how he realized and couldn’t turn away from his attraction to men. It started safe, with magazines and collages and stuff. I love him waking up in the morning and her finding his collages there. It breaks his heart, and it breaks her heart.

It was really cool to hear some of the lines in the film, knowing that they were real. It was like hearing Mapplethorpe say them...

I mean, Matt Smith is just an amazing. He hadn’t done anything more than Dr. Who, and my son, who was nine at the time, said this guy has to be Mapplethorpe. I said, sure.

What was your process like with Matt?

Matt loves a surprise and there is nothing more that a director wants than surprises. Matt loves to live in the moment and discover what the character is gonna do, and try different things. He loved giving me different shades of a color in every take, because it kept him interested and kept it all very alive. And if something didn’t make sense to him in the writing, sometimes on the day, we’d have a debate. Ultimately, we’d try it my way and then we’d try it his way. We really worked as colleagues. I appreciated his intelligence and his spontaneity. He’s a brilliant imporizational artist. I love, as a documentarian, anything that feels like it comes from that magical space. My job really was to impart where I was coming from as a writer and what I envisioned as a director in the space and create a safe space to play. And they did. I mean, Sam Wagstaff (John Benjamin Hickey) was absolutely incredible. And he made Matt feel really comfortable. John being a gay man in real life was a guide to Matt, who has played gay before, but is not gay— they had a good relationship off set. They just got along really well. And Milton Moore played by McKinley Belcher III, man…

Did Mapplethorpe suffer with his muses feeling like they weren’t important? Sam was very diplomatic, but in the film, Milton became upset, how real was that?

Yeah. he wanted to shape Milton like he had been shaped by Sam. Sam had groomed him for success. It was coming from a good place, but it was also him trying to shape this man he found attractive into his fancy lifestyle with his fancy friends. The most successful relationships are when you can accept someone for who they really are, and he couldn't do that.

Matt had a real arc as Mapplethorpe. He starts off demure when he meets Patti, he’s figuring it out, and as he becomes more successful, he becomes more confident, even irreverent with his HIV status. You weren’t afraid to paint him in a bad light?

I heard he was called the prince of darkness from a woman who lives in his loft now, 24 Bond. (That shot on his fire escape is actually on his old fire escape). I was talking to her, and she talked about riding the elevator with him. “You would feel it,” she said, “that he was the prince of darkness. He was so charming and so lovable and so dark. So dark.” My question was, how much did he blame himself for choices that he made? In his view, he chose to be gay. And in his Catholic view, he chose to go to hell. So he looked at everyone else with HIV as if they perhaps made the same choice. And he did intentionally spread it. That’s a hard fact to swallow.

Yeah, he had that line, it’s not my choice it’s theirs. Which is… an intense perspective…

Right. He knew what was going on. Everybody knew. It was the “gay cancer” right? How much was he internalizing some kind of blame being raised by the church and his father? He was just a human. If he was alive today it would be completely different. He was smart. I don’t blame him. I love Robert Mapplethorpe.

I love Sam’s line “Your photos are becoming a gallery of the dead.” There were so many zingers. Robert was so prolific, how’d you sculpt a 102 minute version of his life?

Whatever rang true stayed. The goal of making a film is to get to the truth. That’s it. Sundance Labs taught me that. We are after the truth. That means multiple perspectives. That means grey area. For me, that meant showing three decades. It could not be made in a single moment like many biopics are made. His life was bookended by iconic moments. Coming of age and his HIV.

Catch Mapplethorpe, directed by Ondi Timoner, at Outfest Los Angeles July 13, 2018 with a second screening July 22nd.

Jamison Karon is the author of How to Be a Faggot, and creator of the series and short film Sorry You're Sad. He is a screenwriting fellow at the American Film Institute.